As a Park Ranger at Bryce Canyon National Park I prepared and present a 20-minute Hoodoo geology talk several times a week. Those crazy looking hoodoos is why people visit Bryce.

As a Park Ranger at Bryce Canyon National Park I prepared and present a 20-minute Hoodoo geology talk several times a week. Those crazy looking hoodoos is why people visit Bryce.

The audience area is located about 40 feet from Sunset Point and the Navajo Loop trailhead. Seating is three double rows of wooden benches. Depending on the time of day many visitors either hang out there to sit in shade, not attend a Ranger program, or hover nearby along a fence under a shade tree. It’s awkward.

Look closely for people on the Wall Street trail (phone shot)

Look closely for people on the Wall Street trail (phone shot)

Golden Mantled Ground Squirrel attending program (phone shot)

Golden Mantled Ground Squirrel attending program (phone shot)

Plus, the fenced area along the amphitheater’s rim looks down on the popular Wall Street side of the Navajo Loop trail. In addition, the Sunset parking lot is where tour buses disgorge their hordes of mostly international visitors so the overlook fills quickly and frequently. Have I mentioned that 65% of Bryce’s visitors are international. Some people speak English better than others, some not at all. Always interesting to explain things like not feeding, or putting your fingers near, wildlife like chipmunks and ground squirrels who having been fed are way too friendly with people. Part of my job is to haze the critters away from people, basically stomp my feet and act intimidating. Doesn’t work well or for long. But I digress…

View above Wall Street (phone shot)

View above Wall Street (phone shot)

I get to my presentation area about 15 minutes before start time, right now advertised at 11am or 2pm. Sometimes it’s difficult to tell if anybody is there for a Ranger program. So I chat with folks asking where they are from, and take it from there. Knowing where visitors live in regards to elevation usually tells me I need to make altitude sickness and dehydration my safety talk before getting down to hoodoo geology.

Depending on the season and weather I often add a reminder to stay away from the rim during a nearby lightning storm recommending a vehicle or building as the safest place to be. When thunder roars, go indoors. When you see the flash of a lightning bolt, you can start counting seconds, “One-Mississippi, two-Mississippi, three-Mississippi…” Sound travels 1 mile in roughly 5 seconds and you should be at least 10 miles away from lightning. Finally with small talk and safety message done, usually more people have joined because there’s a Ranger talking.

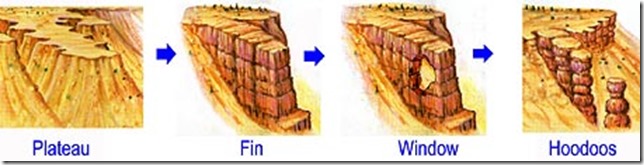

Image shared with audience

Image shared with audience

(borrowed from the internet, although I own the poster and use it in another geology talk)

(borrowed from the internet, although I own the poster and use it in another geology talk)

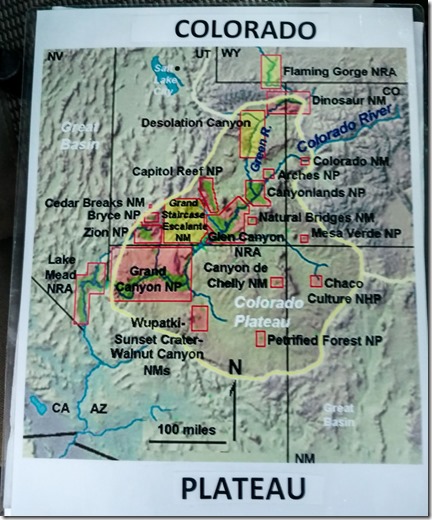

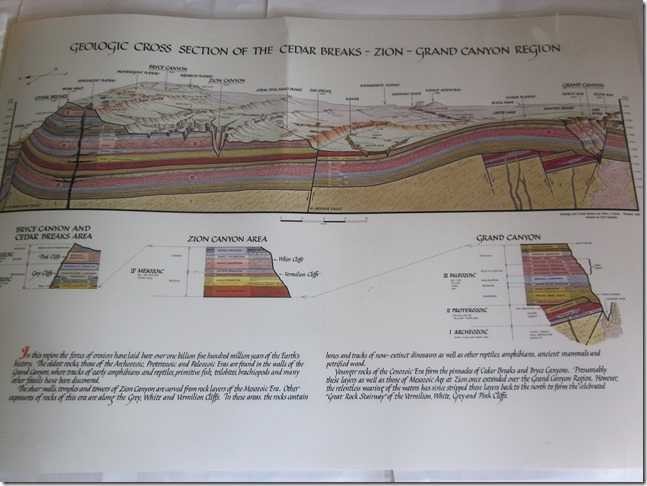

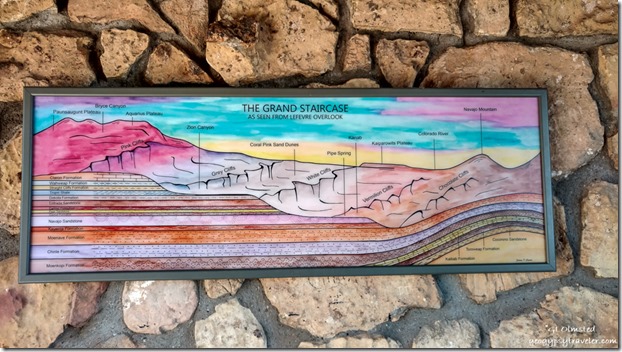

I’m going to talk about how these crazy looking rocks called hoodoos were both created and destroyed by water. But first let’s put Bryce Canyon National Park in perspective on the Colorado Plateau. Going back about 85-60 mya (million years ago) the continent was smaller, no California, and closer to the equator. The floor of the Pacific Ocean, on a separate tectonic plate than the continent, bumped into the continent and subducted below the continental crust. It’s hot down there so that rock melted, became buoyant, and lifted a land mass of 240,000 square miles that straddles some of Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and Colorado at The Four Corners. The slow uplift went from sea level up 7,000 to 10,000 feet with almost a mile of sedimentary rock deposits from oceans, lakes, dunes, estuaries and rivers.

(NPS illustration)

(NPS illustration)

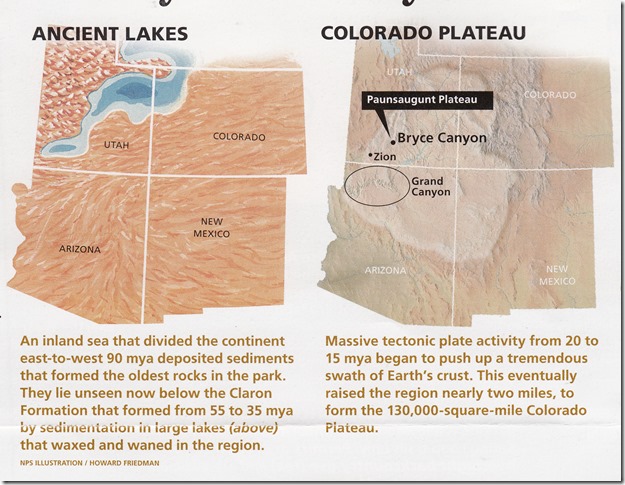

About 60 mya in this location, a dip in the land allowed for a lake to fill. When the tiny creatures living in the lake died their bones and shells fell to the lake bottom, built up, and were compressed into limestone. Rivers and streams flowed into the lake sometimes bringing mud, or sand which was also lithified, or turned into rock, mudstone or shale, sandstone, and then more limestone. Over millions of years the deposits built up to at least 2000 feet thick.

(borrowed from the internet, I use my fists to demonstrate normal faulting)

(borrowed from the internet, I use my fists to demonstrate normal faulting)

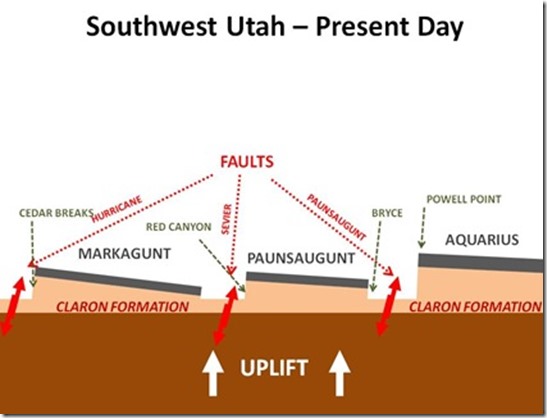

Then, about 16-6 mya, three blocks of land with faults between broke apart leaving the Aquarius Plateau in the east, a valley where the Paria River flows, the Paunsaungunt Plateau where Bryce is, the Sevier River Valley, and the Markagunt Plateau to the west. The Paunsaungunt is about 1000 to 2000 feet lower than the other two plateaus. Yet the lake deposits are the same so hoodoos can also be seen at Cedar Breaks National Monument, just in smaller concentration than Bryce. Imagine all the shaking of the earth during this faulting.

I most often use my hands to demonstrate (lousy hand selfie)

I most often use my hands to demonstrate (lousy hand selfie)

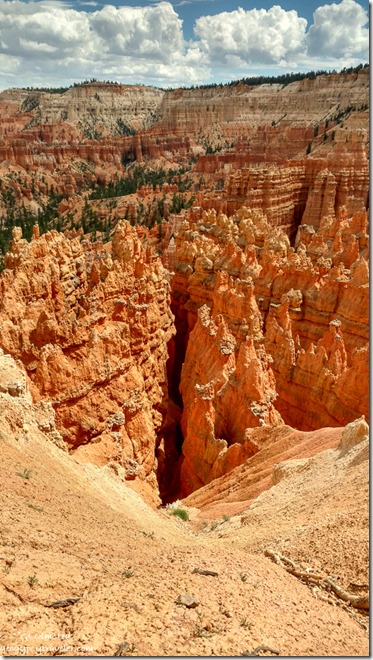

OK, now on to the formation of hoodoos. Bryce receives about 16 inches of precipitation a year. Water flows off the plateau following the line of least resistance and finds cracks and fractures. The water erodes the land backwards, called headward erosion, and leaves walls of rock. The rate of erosion is about one foot every 50 years. That’s fast. In some areas of the park old rim trails are closed and new railings are parallel to the old because of that fast rate of erosion. Think about it, 50 years compared to the 85 million years where I started this story.

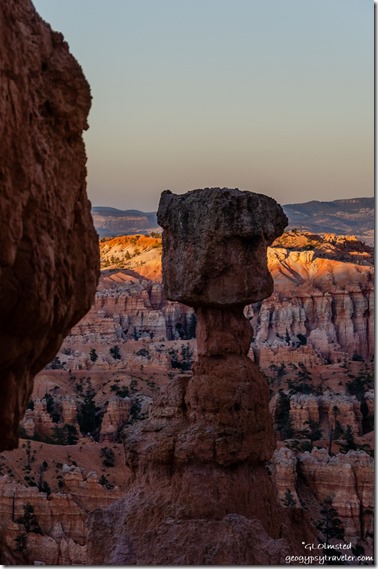

Note the skinny hoodoos still have some gray dolomite cap rock

Note the skinny hoodoos still have some gray dolomite cap rock

I use my hands for this demonstration also (borrowed from internet)

I use my hands for this demonstration also (borrowed from internet)

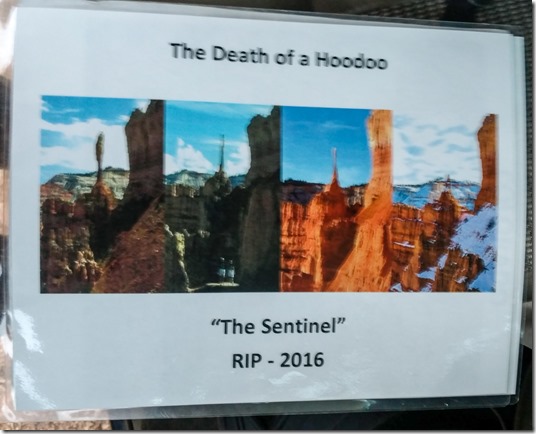

Now, there are walls of fractured, soft, sedimentary rock – mostly limestone with intermittent layers of sandstone and mudstone – and they are capped by dolomite, a harder layer of limestone which protects the softer layers below, for a while anyway. Sort of like me wearing a hat that keeps my glasses dry in the rain. The narrowest area is the softest mudstone. At 8000 feet in elevation, Bryce receives about 200 nights below freezing. When the water in the vertical cracks in the walls freezes it expands forcing the rocks apart, called frost wedging. Over time the wall can become a window. Eventually the cap rock falls and leaves pillars of rock standing side by side. Then erosion from wind, rain and snow softens the shapes into hoodoos. But they don’t stand forever, slowly shrinking into a rounded pile of dirt. The average life of a hoodoo is 2000 years.

Grand Staircase painting at Le Fevre overlook Kaibab NF AZ

Grand Staircase painting at Le Fevre overlook Kaibab NF AZ

But what about the color? In the early 1870s, geologist Clarence Dutton named these rocks at the top of the Grand Staircase the Pink Cliffs, also known as the Claron Formation. I struggle with pink, seeing mostly shades of orange. Maybe Clarence saw them in a different light, or maybe he was colorblind. Iron is present in the sediments and oxidation makes for the colors.

Walls of hoodoos in the Silent City (phone shot)

Walls of hoodoos in the Silent City (phone shot)

The word Hoodoos is fun to say, go ahead ‘who-do’. I have discovered different origins for hoodoo. Coming from the southeastern US where 1800s African slaves practiced a folk magic called hoodoo. One band of native Paiute tell a story of the rocks being bad people turned to stone by the trickster coyote. Yet when recently talking to a group of Paiute youth with elders I was told the word is ‘oodoo’ – no “h” – and means neither bad nor good.

The once famous Sentinel hoodoo over ten years time was struck by lightning

The once famous Sentinel hoodoo over ten years time was struck by lightning

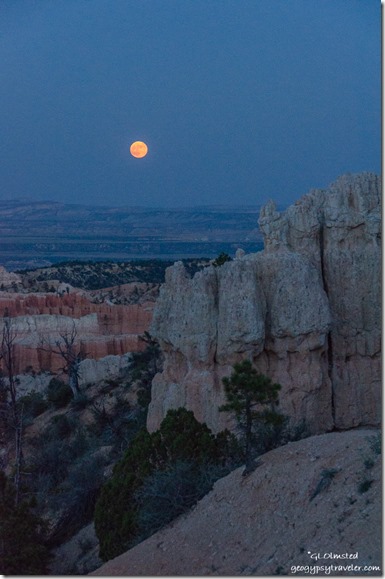

So, hoodoos come and hoodoos go, all created by and destroyed by water. Headward erosion will continue to create walls until there is no plateau left. Of course, not in our lifetimes. Changing climate may also change the rate of frost wedging. Will there be a Bryce Canyon National Park someday in the geologic future?

The above is one out 1100 photos of the inside of my back pocket from my phone the day I took many of the above photos and presented my talk about Hoodoo geology. Oops. Kind of a fun pattern though.

The above is one out 1100 photos of the inside of my back pocket from my phone the day I took many of the above photos and presented my talk about Hoodoo geology. Oops. Kind of a fun pattern though.

I

I