Many people make a big deal about going to see The Wave, struggling to get one of the 20 daily permits. Yet Coyote Buttes North in the Paria Canyon-Vermilion Cliffs Wilderness is so much more than just the “feature” as Bill calls it.

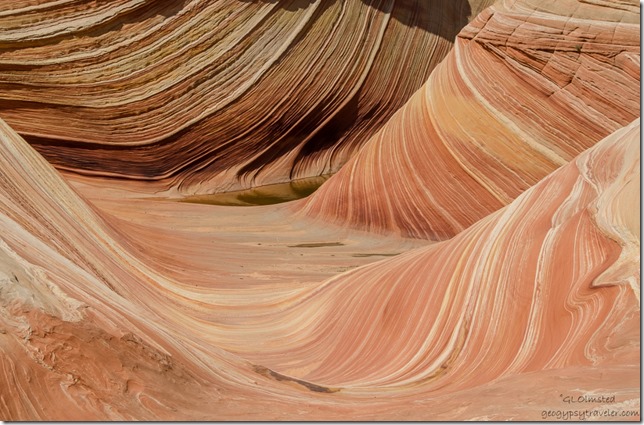

After the 3.7 mile hike from Wire Pass Trailhead through dry wash, sand and over contoured slick rock we approached The Wave with its sinuous lines of sandstone, like many others we’ve passed.

After the 3.7 mile hike from Wire Pass Trailhead through dry wash, sand and over contoured slick rock we approached The Wave with its sinuous lines of sandstone, like many others we’ve passed.

Looking back I could barely believe we made it. But we’re really not there yet.

Looking back I could barely believe we made it. But we’re really not there yet.

We had yet to walk around the water and look at the feature and beyond.

We had yet to walk around the water and look at the feature and beyond.

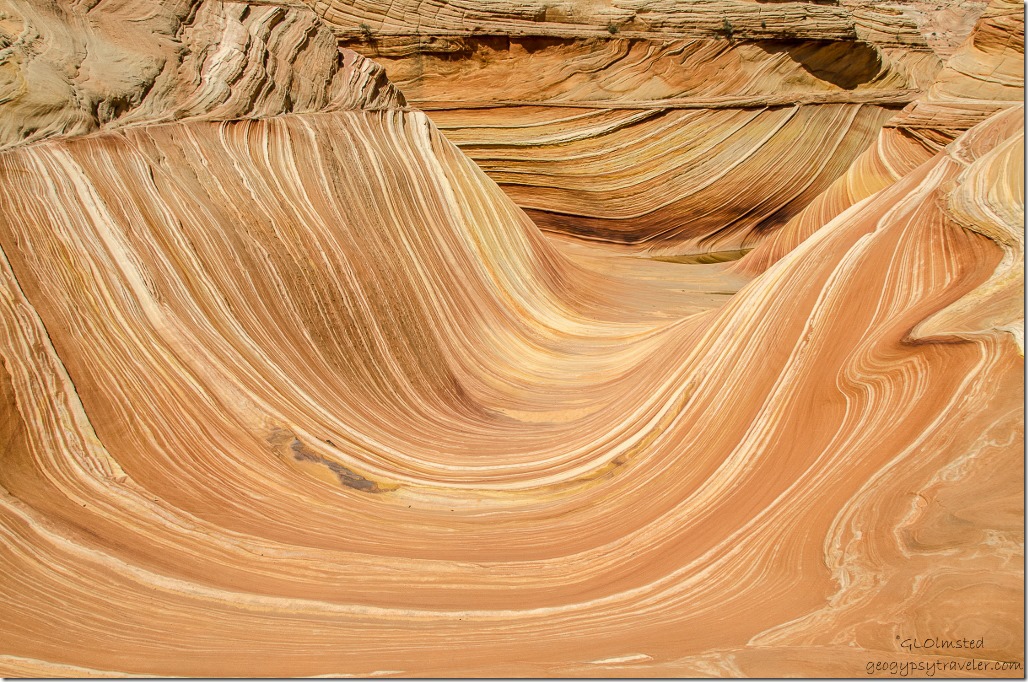

How to describe The Wave? Bands of mineral colors flow over the sandstone mounds worn by eons of water and wind. Nature’s art at its best. But why is it all about The Wave? Everywhere I looked there was so much beauty.

How to describe The Wave? Bands of mineral colors flow over the sandstone mounds worn by eons of water and wind. Nature’s art at its best. But why is it all about The Wave? Everywhere I looked there was so much beauty.

Bill first visited the as yet unnamed Wave in 1977, a year after starting his position with BLM (Bureau of Land Management) in Kanab, Utah. This feature was known to only the few people who lived relatively nearby. He visited the landscape a number of times. During the wilderness inventory three years later in Utah, Coyote Buttes North was included due to wilderness character. Later, while National Geographic put together the book Our Threatened Inheritance they sent a photographer with BLM employees who took them over Davis Pass to the feature, during the winter, under a promise of not disclosing the location of the area. Yet when the story and photo proofs came out it was labeled “Coyote Buttes” and under insistence from BLM the name was dropped and the location was only alluded to. The Paria Canyon-Vermilion Cliffs Wilderness was established in 1984 and a plan was created to allow only two groups of four into the feature daily.

Bill first visited the as yet unnamed Wave in 1977, a year after starting his position with BLM (Bureau of Land Management) in Kanab, Utah. This feature was known to only the few people who lived relatively nearby. He visited the landscape a number of times. During the wilderness inventory three years later in Utah, Coyote Buttes North was included due to wilderness character. Later, while National Geographic put together the book Our Threatened Inheritance they sent a photographer with BLM employees who took them over Davis Pass to the feature, during the winter, under a promise of not disclosing the location of the area. Yet when the story and photo proofs came out it was labeled “Coyote Buttes” and under insistence from BLM the name was dropped and the location was only alluded to. The Paria Canyon-Vermilion Cliffs Wilderness was established in 1984 and a plan was created to allow only two groups of four into the feature daily.

We’d been told not to disturb the pools to protect rare desert species. Who’d have thought we’d see tadpoles the size of golf balls.

We’d been told not to disturb the pools to protect rare desert species. Who’d have thought we’d see tadpoles the size of golf balls.

So we skirted around the water climbing on the rock and just around the corner, there it was, The Wave. We climbed to the top for the better view looking down. Other hikers were polite about taking photos and then staying out of each others views.

So we skirted around the water climbing on the rock and just around the corner, there it was, The Wave. We climbed to the top for the better view looking down. Other hikers were polite about taking photos and then staying out of each others views.

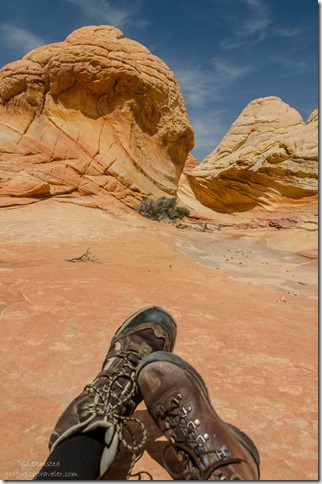

Three young German visitors had hiked past us on the way in and we saw them again when we arrived along with three others sitting in the little bit of shade offered by a sandstone wall near the pool. We took our turn and I posed at the top ready to surf down The Wave.

Three young German visitors had hiked past us on the way in and we saw them again when we arrived along with three others sitting in the little bit of shade offered by a sandstone wall near the pool. We took our turn and I posed at the top ready to surf down The Wave.

A last look before climbing higher up to have lunch in the shade of a giant sandstone boulder. Must have been close to 100F (38C).

A last look before climbing higher up to have lunch in the shade of a giant sandstone boulder. Must have been close to 100F (38C).

That pool of water looked mighty inviting.

That pool of water looked mighty inviting.

Bill had concerns about the site being over visited. Motivated by a proposal to increase fees he became a volunteer so he could access and report any possible problems. It’s not so much the feature as the surrounding area and it’s difficult to impossible to visit because only 20 permits are issued per day. He was curious about how the site was withstanding a steady visitation even if it’s limited, if impacts and changes were occurring. Of course, for safety purposes I went with him.

Bill had concerns about the site being over visited. Motivated by a proposal to increase fees he became a volunteer so he could access and report any possible problems. It’s not so much the feature as the surrounding area and it’s difficult to impossible to visit because only 20 permits are issued per day. He was curious about how the site was withstanding a steady visitation even if it’s limited, if impacts and changes were occurring. Of course, for safety purposes I went with him.

Except for some of the signage going in and footprints on sandy areas he didn’t notice any visible damage. We picked up only three pieces of micro-trash. People seem aware and respect the landscape. He was pleasantly surprised and had thought it would have been more impacted.

Except for some of the signage going in and footprints on sandy areas he didn’t notice any visible damage. We picked up only three pieces of micro-trash. People seem aware and respect the landscape. He was pleasantly surprised and had thought it would have been more impacted.

Wilderness is suppose to provide opportunities for primitive and unconfined recreation with solitude and a connectedness to the landscape which could be negatively impacted by over visitation. How many of us truly get a chance to experience wilderness?

Wilderness is suppose to provide opportunities for primitive and unconfined recreation with solitude and a connectedness to the landscape which could be negatively impacted by over visitation. How many of us truly get a chance to experience wilderness?

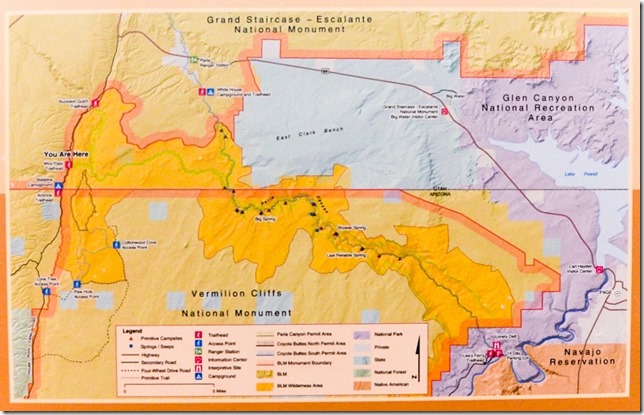

And this wilderness is vast, covering 112,500 acres with so much space we should be able to immerse ourselves and never see another person. Unfortunately this feature has been heavily promoted and focuses people to just one small piece of this hugely delicious pie.

And this wilderness is vast, covering 112,500 acres with so much space we should be able to immerse ourselves and never see another person. Unfortunately this feature has been heavily promoted and focuses people to just one small piece of this hugely delicious pie.

In fact pie would have tasted extra good for lunch but instead we settled with PBJ on flat bread, chips and olives along with copious amounts of water in a sliver of shade leaning on a huge sandstone formation.

In fact pie would have tasted extra good for lunch but instead we settled with PBJ on flat bread, chips and olives along with copious amounts of water in a sliver of shade leaning on a huge sandstone formation.

We had planned to explore beyond the feature but instead sat and absorbed the 360 degree views. Until the shade disappeared and we could really feel the heat. That’s when I couldn’t resist the water and soaked my shirt before heading back to the feature and the return hike. We were both very careful not to disturb any creatures.

I’ll bet land-forms every bit as intriguing as The Wave exist in this vastly unique sandstone terrain. Yet with no camping in the Coyote Buttes Wilderness I’d have to be a faster hiker to journey much further.

I’ll bet land-forms every bit as intriguing as The Wave exist in this vastly unique sandstone terrain. Yet with no camping in the Coyote Buttes Wilderness I’d have to be a faster hiker to journey much further.

Bill made the walk around the pool look easy but I struggled a bit. That sandstone is more slippery than it looks.

Bill made the walk around the pool look easy but I struggled a bit. That sandstone is more slippery than it looks.

The pools of water look just as foreign to the land today as they would have millions of years ago when these rocks were sand dunes.

The pools of water look just as foreign to the land today as they would have millions of years ago when these rocks were sand dunes.

The return walk went a little quicker.

The return walk went a little quicker.

Bill spotted two shallow pools of water to re-soak our shirts and they were dry in about 10 minutes.

Bill spotted two shallow pools of water to re-soak our shirts and they were dry in about 10 minutes.

Even though I’d paid close attention looking behind me on the hike in I saw the landscape with different eyes on the way back. The map with photos showed landmarks for the return that were easy to spot and although I led the way in Bill lead the way out.

Even though I’d paid close attention looking behind me on the hike in I saw the landscape with different eyes on the way back. The map with photos showed landmarks for the return that were easy to spot and although I led the way in Bill lead the way out.

Left the trailhead at 8:30am, arrived at The Wave at 11:45, after lunch, and of course more photos, left at 2pm and got back to the truck at 5.

Left the trailhead at 8:30am, arrived at The Wave at 11:45, after lunch, and of course more photos, left at 2pm and got back to the truck at 5.

I have to agree with Bill, the Paria Canyon-Vermilion Cliffs Wilderness is so much more than just The Wave. Every step along the trail brought new wonders of rock and far views. And we barely scratched the surface of what this wilderness landscape has to offer.